Do you consider yourself woke? A recent article in TODAY stirred a lot of criticism regarding “wokeism” and “cancel culture” – particularly the part where it touched on transgender.

If you haven’t read the article, here’s a TLDR version: the author suggests that people are pretending to be “woke” in order to not be cancelled. She used her own experience of not daring to “ask questions” regarding trans people in order to “fit in” with the woke crowd.

Why is being “woke” so important?

Defined as “aware of and actively attentive to important facts and issues (especially issues of racial and social justice),” it’s no surprise that many – especially the young – see that being “woke” to such problems is a good thing.

Why? Because the human ego is a sneaky thing – being “woke” is like having the moral high ground. So now, in addition to race, sex, intelligence, and religion, we’ve added “woke” to the assessment of superiority. This can be a slippery slope.

A danger of “wokeism” is when people who are “woke” call out or “cancel” those they perceive not to be woke (or woke enough) – and this can be damaging to one’s reputation. Consequently, today’s detractors claim that rejecting the idea of being “woke” means rejecting “cultural elitism.”

However, rejecting this “cultural elitism” has turned “wokeism” and “cancel culture” into a weapon, as Malorie Blackman highlighted in her viral tweet, writing: “’Woke’ means alert to social injustice. Watch as those with a negative agenda try to spin ‘woke’ into a pejorative term, an insult.”

And this is precisely the issue with the article we’re grappling with.

The transgender issue

The author openly admits to not knowing much about transgender issues, but is afraid of asking people. She raised the example of JK Rowling’s tweet about trans women as reason for being afraid to admit that she still has questions and discomfort about openly transgender people:

- “But I can’t even admit that I’d like to know! Because now, even asking can be construed as disagreeing or being unsupportive of “the cause”, and thus, offensive.”

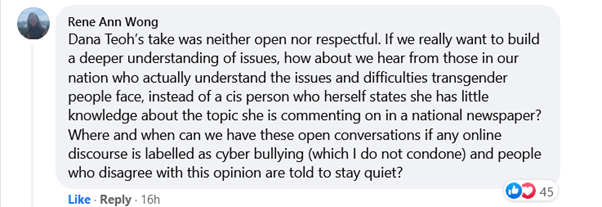

In her argument, apparently simply asking for an explanation is “offensive.” But to many, it simply shows zero willingness for her to try to learn about the people by whom she feels “weirded out”:

- “I still get weirded out by photos of post-op bodies, and still struggle with the argument that trans children should be given hormone blockers.”

By making the argument about “cancel culture” and “wokeism” crumbling away at healthy discourse in our society, it feigns concern for trans people and ironically reduces them to a talking point in the argument:

- “And that doesn’t help the trans community at all. All I’d be doing is pretending to understand and embrace all their choices, a facade erected to mask how ignorant and uncertain I actually am.”

Her decision to use “woke” as a shield to deflect the argument away from her “ignorance” of transgender issues is a major reason for the article getting viral.

The new FOMO

Forget FOMO, FOBC – Fear of Being Cancelled – could be the next big thing. In essence, the article seems to blame “the woke” for indirectly pressuring those who are in the dark about certain issues to conform blindly.

If this debate seems a little Orwellian, it’s probably because the article suggests that the word “woke” – something that was originally about protecting minorities – now symbolises a threat to free speech.

- “Being woke isn’t just being sensitive or caring. It also encourages narrow-mindedness, and refuses to acknowledge, let alone respect, even the mere suggestion of differences in opinion.”

It’s painted as a ‘”damned if I do, damned if I don’t” scenario. Speaking our mind, which is so rife in the age of social media, can apparently be silenced by the fear of getting “cancelled”.

It was written as a university assignment

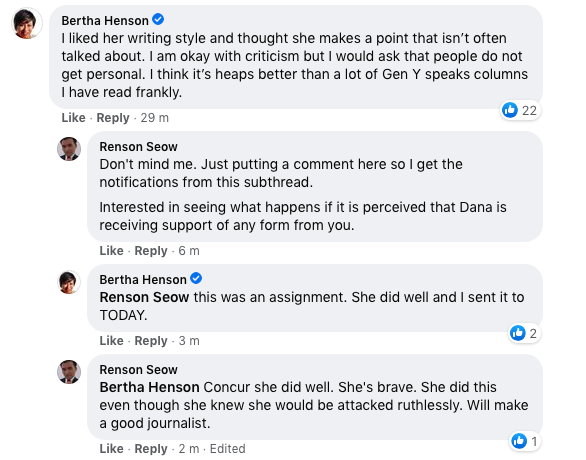

The author actually wrote this piece for a university assignment and it was her teacher – Bertha Henson – who sent it to the press, who published it.

Naturally when the piece came out, viewers were split into two camps (one pro, one against). One commenter lauded her bravery – certainly a virtue in journalism – even going so far as saying that being “attacked ruthlessly” makes one a good journalist.

If that was the case, wouldn’t a good journalist not be afraid to ask questions in order to be more informed? Shouldn’t she brave the risk of getting “cancelled” in order to seek the truth or understand the issues she’s unclear about? Even she herself stated:

- “However, I would like to know what someone else — who may be very different from me — thinks about an issue as novel as trans rights and transphobia. Someone who’s trans, maybe.”

Instead, she chooses to write about her fear of transgenders and being cancelled to be the hill she dies on – something she must have known could result in equal parts glory and ignominy.

Under the cover of woke-ness

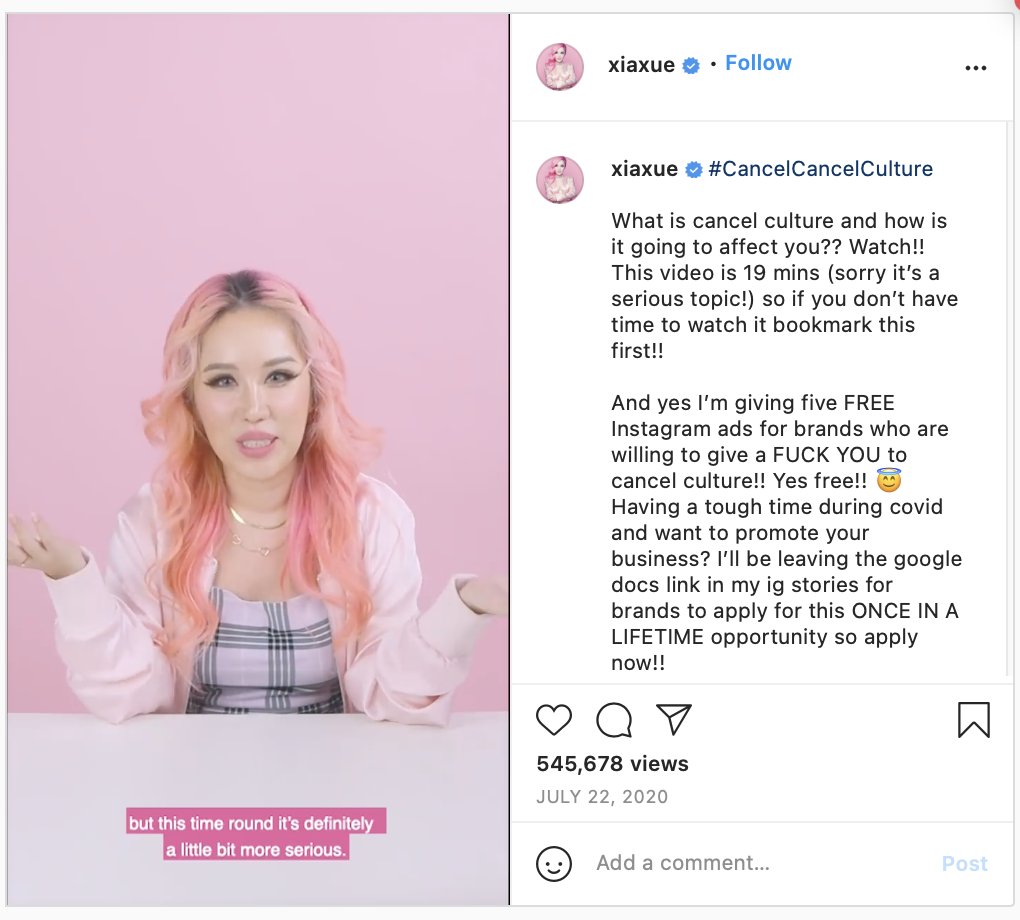

This piece exposes how “woke” is a double-edged sword. In the same way some feel compelled to be “woke” to avoid social stigma, on the other end of the spectrum, “woke” has also been weaponised as a buzzword for hate-preachers – as the new “snowflake”.

On that side of the spectrum, focusing on “wokeism” and “cancel culture” is becoming a roundabout way to defend bigotry, racism, LGBTQ-phobia, and other hard issues – it’s a classic red herring fallacy.

In this case, by criticising “woke culture,” the author claimed victim status for herself rather than acknowledge that more deserving others hold that status.

Then again, to focus on this piece – and the author – would be to miss the forest for one tree. There are many others who definitely hold sizeable influence around this issue.

This whole issue just shows that we should be careful not to use “woke” and “cancel culture” to blur the lines between being bullied and taking responsibility for the consequences of actions or words.